I write about investing, business breakdowns, and growth philosophies. Join over 8,000 Steady Compounders by subscribing here:

At this point, I’m sure all of you have heard of the company Alibaba and its celebrated founder Jack Ma. Especially after Jack’s notorious speech on 24 Oct 2020, criticizing the banking system and likening the current banking regulations as a treatment for Alzheimer’s.

He argued that innovations aren’t afraid of regulations, but you cannot use the methods of yesterday to manage the future—that you can’t manage the airport with the same method of managing railway stations. Jack continued, “the future of competition is an innovative competition, not just a competition of supervision skill.”

Oof. Savage.

This was but a slice of what the speech entails. No wonder that the Western media scurried to fill the headlines insinuating that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) made Jack Ma disappear after the speech or that they’re breaking up Ant Financial because of his speech.

Neither of them are true.

Jack Ma is still well and alive today and the issue with Ant Financial’s IPO arose before Jack Ma’s speech, as regulators were concerned with its lending operations: Huabei and Jiebei, which means “just spend” and “just borrow”.

With the media picking apart Alibaba’s outlook, the share price has tumbled. Famed value investors such as Charlie Munger, Thomas Russo, Mohnish Pabrai, Guy Spier, Robert Vinall have thrown their hat into the ring and taken sizeable positions in Alibaba.

What we do when the market is going on a free fall is what defines us as investors. After all, a rosy outlook and cheap valuations never go hand-in-hand, and in moments like this, we have to decide whether this saga is a permanent impairment to Alibaba’s economic engine, or is it just a temporary blip.

The Alibaba Ecosystem

Alibaba’s ecosystem spans across the entire e-commerce value chain, from branding to broadcasting, sales conversion, sharing and payments.

This is very different from how it works in the U.S., where a seller chooses to sell on Amazon or Shopify and go to Facebook to advertise their product, design their marketing collaterals on Fiverr, and use Stripe or Adyen for payments. Each internet giant is individually dominant in certain parts of the value chain.

For Alibaba, it dominates that entire value chain.

In China, there are two companies that you absolutely can’t live without, Alibaba and Tencent.

Alibaba runs commerce and Tencent runs communications & entertainment.

Let’s dive deeper into Alibaba’s commerce

Commerce

Alibaba’s core commerce business is comprised of the following:

- Retail commerce – China

- Wholesale commerce – China

- Retail commerce – cross-border and global

- Wholesale commerce – cross-border and global

- Logistics services

- Consumer services

Retail commerce – China

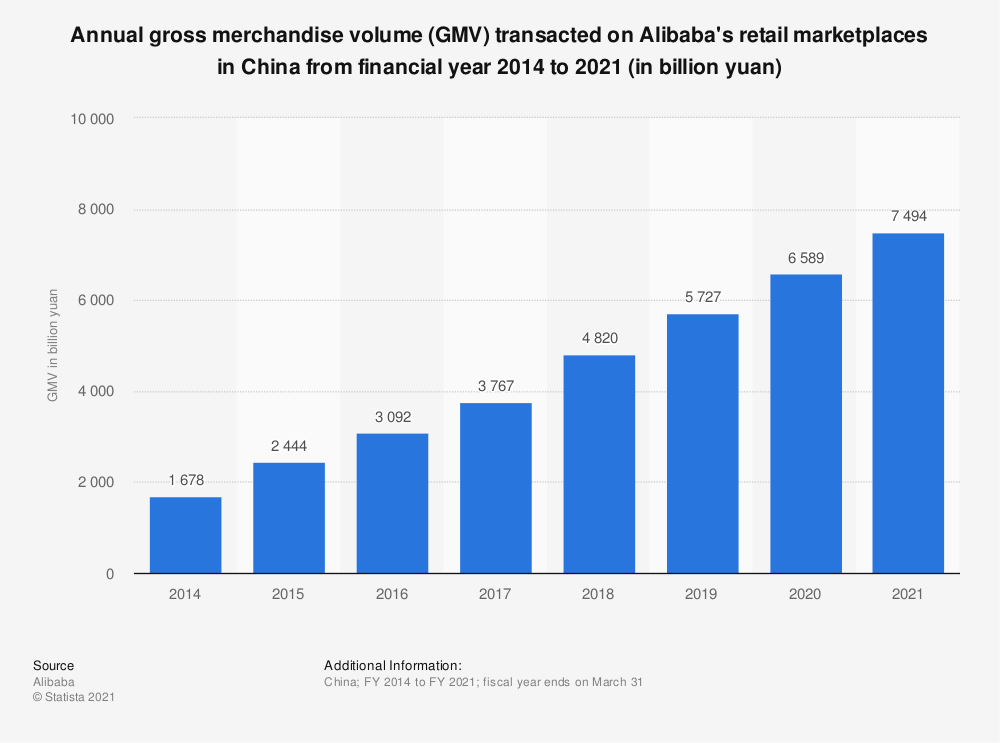

Alibaba operates the world’s largest retail commerce business in the world when measured by Gross Merchandise Value (GMV), i.e. the dollar amount of products sold on its platform.

In the fiscal year ending 31 Mar 2021, approximately $7.49 trillion yuan ($1.17 trillion USD) transacted on the platform! To put this in perspective, Amazon did $475 billion, Shopify did $120 billion, eBay did $100 billion and Etsy did $10.28 billion in 2020. Even Alibaba’s two core domestic competitors, JD.com and Pinduoduo did $62 billion and $40 billion.

Taobao, the consumer-to-consumer social commerce platform, and Tmall, the commerce platform for brands and retailers, are the two core consumer businesses that makeup 66% of Alibaba’s total revenue. Unlike Amazon, Taobao and Tmall carry no inventory. They serve as platforms for other merchants to sell their products.

Under the umbrella of China’s retail commerce, there is also their New Retail initiatives, which is to transform traditionally offline retailing such as groceries, real estate, home furnishings, and pharmaceuticals into a hybrid format of online and offline models. While there’s a lot of hype since it was initiated in 2016, its success remains to be seen.

Taobao

Taobao is similar to eBay, except that most of the items sold are new, not second-hand. It’s built to serve millions of “micro-merchants” and there are no fees charged for selling on the platform. But Taobao makes money—plenty of it—from selling advertising space, promoting those merchants who want to stand out from the crowd.

Merchants can advertise through paid listings or display ads. The paid listing model is similar to Google’s AdWords, where advertisers bid for keywords to give their products a more prominent placement on Taobao. Merchants pay Alibaba based on the number of times consumers click on their ads. Alternatively, they could use a more traditional advertising model, paying based on the number of times their ads are displayed on Taobao.

Fun fact: Alibaba’s client service managers are referred to as xiaoer (小二), which is affectionately known as service staff back in the olden days. Thousands of xiaoer mediate any disputes that arise and are empowered to shut down a merchant if they don’t comply with Taobao’s rules or to reward merchants by promoting their digital store for free.

Taobao’s success is also largely due to its vibrant platform, which acknowledges that Asian shopping is a highly social and interactive activity. Customers can use Alibaba’s chat application to haggle prices, even over video chats! Most packages also arrive with free gifts and a thank you note.

Tmall

While Taobao is a collection of “micro-merchants”, Tmall is a glitzy shopping mall that houses large retailers and luxury brands. Unlike Taobao, selling on Tmall is not free! Merchants pay commissions to Alibaba on the products, ranging from 0.3% to 5% depending on the category.

Tmall hosts three types of stores on its platform:

- Flagship stores: Run by a brand itself

- Authorized stores: Set up by a merchant licensed to do so by the brand

- Specialty stores: Carry goods of more than one brand.

There’s a huge range of brands on Tmall, similar to what you will see in a giant shopping mall. Its most popular brands include Nike, Gap, Uniqlo, L’Oréal, Xiaomi, Huawei and Haier.

Mobile monthly active users (MAUs) refers to the number of unique mobile devices that access their mobile apps at least once during the month.

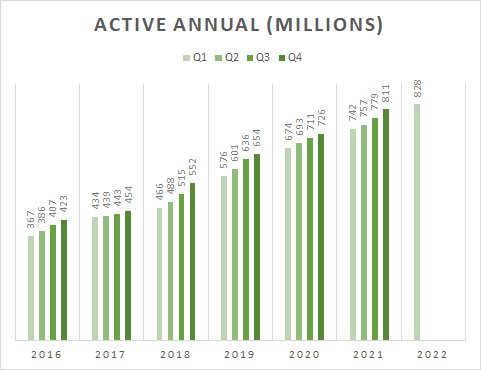

Annual active consumers” refers to the number of users that placed one or more confirmed orders.

When we look at these numbers, it is clear that anyone with a mobile phone in China would access one of Alibaba’s apps every month. Tmall has definitely become a hard-to-replace service for consumers.

New Retail Initiatives

While e-commerce is great, there’ll always be certain products and services that could be better served offline, and Alibaba is looking to dominate this aspect of commerce as well.

The new retail is a concept developed by Jack Ma in 2016, who wants to combine online, offline, logistics and data across a single value chain to give consumers more personalized shopping experiences.

The supermarket is one such example, where consumers in Asia prefer to handpick out their produce in stores as it allows them to judge the food quality. The pain point here is that no consumers would enjoy queueing and carrying the heavy groceries back. Here is where Alibaba attempts to solve the problem by enhancing the traditional supermarket digital capabilities and logistical capabilities.

In 2020, Alibaba spent $3.6 billion to increase its stake in the leading hypermarket operation Sun Art to 72% and turned it into a subsidiary. Sun Art has integrated its 484 physical retail locations into Alibaba’s Taoxianda and Tmall Supermarket platforms for groceries, as well as Ele.me and Cainiao, its on-demand food delivery apps and logistics businesses, respectively.

Together with Freshippo, a membership grocery retail (akin to Costco), Sun Art is now Alibaba’s main platform for carrying out its New Retail initiative. Consumers can now easily find out the source of the fresh produce by scanning QR codes or skip the line by depositing the produce and having it delivered within 30 minutes to a few hours depending on the proximity.

These initiatives go beyond groceries, Alibaba has extended it to car showrooms, pharmaceuticals, home furnishings, mom-and-pop stores and more.

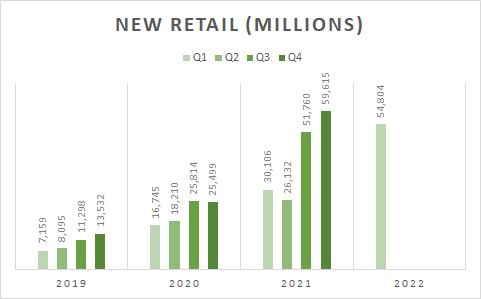

We can see from Q3 2021, there was a huge bump in revenue due to the consolidation of Sun Art’s results into their financial statement. The rapid growth in new retail is expected to drag down the overall margins of Alibaba due to the need to maintain logistical capabilities and storefronts. This will be covered further down in the report.

Wholesale Commerce – China

For their wholesale marketplaces, revenue is primarily driven by the number of paying members, membership renewal rates and other value-added marketing services provided to members.

Alibaba’s China wholesale business has two arms: (1) 1688.com, and (2) Ling Shou Tong. Together they make up for approximately 2% of Alibaba’s revenue.

1688.com

With close to 1 million paying members, 1688.com is China’s leading domestic wholesale marketplace. It provides direct sourcing for merchants by connecting wholesalers and merchants on its marketplace, Alibaba makes it possible for producers to shorten the distribution chain and for retail merchants to have access to a more cost-effective direct sourcing channel.

Ling Shou Tong

Ling Shou Tong is a platform that connects fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) brand manufacturers directly to small retailers such as mom-and-pop stores. Currently, Ling Shou Tong offers seamless inventory management to over 20% of small retailers and allows shop owners to restock directly from Alibaba through digital payments and one-day delivery.

Moreover, the system empowers small retailers by providing them with data-driven insights into sales trends, inventory recommendations, and supplier credit to finance inventory and other products such as airtime.

For customers, Ling Shou Tong creates convenience by blending physical and online commerce, for example, by leveraging physical retail merchants as last-mile delivery and drop-off points for e-commerce purchases and returns or by enabling customers who find something out of stock in the physical retail store to simply have it delivered later via the e-commerce channel.

Ling Shou Tong is offered free to these small merchants. Alibaba’s aim is to gain access to the large portion of retail sales that are made offline where Alibaba has traditionally been excluded. It generates huge amounts of data that it can use to drive its other services.

Retail Commerce – Cross-Border and Global

There are four platforms for Alibaba’s global retail commerce: (1) Lazada, (2) AliExpress, (3) Tmall Global, and (4) Trendyol.

Lazada (Southeast Asia)

For overseas, they operate Lazada, an e-commerce platform in Southeast Asia (SEA) which is a direct competitor of Shopee (do check out the Deep Dive report of Shopee if you haven’t!). They were the leader in the region when Alibaba acquired the company but ceded their position to Shopee.

The battle is still ongoing in the region and Lazada has copied Shopee’s playbook, such as using celebrity endorsement and gamifying the shopping experience.

More importantly, they are aspiring to be a super app in the region. It is especially important to do this in Southeast Asian countries such as Indonesia, where the vast majority of the population only has access to low-end smartphones and can only run 5 to 6 apps at a time without it lagging. Hence, to be an app worthy of installation, you have to provide multiple use cases.

I learned this from speaking with a Grab executive on why they merged their ride-hailing app and their food delivery app. Their largest market, Indonesia was facing this issue and they had to merge all their services under the Grab app.

Back to Lazada, they have integrated the ride-hailing service of Singapore transport firm ComfortDelGro on the app’s home page.

They also added a flight-booking feature in 2020 for its users in Singapore and the Philippines.

Lazada users in Indonesia and the Philippines can pay bills and top-up phone credits. In Vietnam, Lazada also formed a partnership to integrate both companies’ offerings onto their respective local platforms. With the tie-up, Vietnamese users can access on-demand meal delivery service GrabFood from the homepages of Lazada’s app and website. Lazada’s platform can also be accessed through links embedded in Grab’s campaign banners.

Is the market too saturated? My view is that the Southeast Asia market is large enough for several players to thrive. In Indonesia, it’s likely that Shopee, Lazada and GoTo will continue to dominate the e-commerce scene.

AliExpress

Then there’s AliExpress, which is Alibaba’s global marketplace and has a big presence in countries such as Russia, the United States, Spain, France, and Brazil, among others. It allows consumers from around the world to buy directly from the manufacturers and distributors in China and around the world.

If you have heard of the term dropshipping, AliExpress is a key enabler of this business model.

With Amazon and Shopify powering up e-commerce in other parts of the world, many dropshippers will ship their products to Amazon warehouses through their “fulfilled by Amazon” program where they carry the inventory. And when their customers order through Amazon, the company will automatically ship out their products.

We see this happening in e-commerce sites all over the world, where the merchants typically buy in bulk from AliExpress and sell at a markup on other e-commerce platforms.

Tmall Global & Tmall World

Tmall Global allows overseas brands and retailers to engage with and sell to consumers in China and is the largest import e-commerce platform in China based on GMV. Also, in Sep 2019, Alibaba acquired Koala, another import e-commerce platform in China to broaden their offerings and strengthen their leadership.

Additionally, there’s Tmall World, a Chinese-language e-commerce platform that allows overseas Chinese consumers to shop directly from Chinese domestic brands and retailers.

Trendyol and Daraz

Alibaba also operates Trendyol in Turkey, and Daraz, which primarily operates in Pakistan and Bangladesh. Turkey is the 20th largest e-commerce country in the world.

Collectively, Alibaba’s cross-border businesses make up about 7% of total revenues.

Logistics Services

Alibaba operates Cainiao’s Network’s logistics data platform and global fulfillment network. It offers domestic (i.e. China) and international one-stop-shop logistics services and supply chain management solutions.

Cainiao Network’s data insights and technology facilitate the digitalization of the entire warehousing, fulfillment and delivery process, which enhances efficiency across the logistics value chain.

In addition, they also operate Fengniao Logistics to deliver food, beverages, groceries, among other products, to consumers on a timely basis.

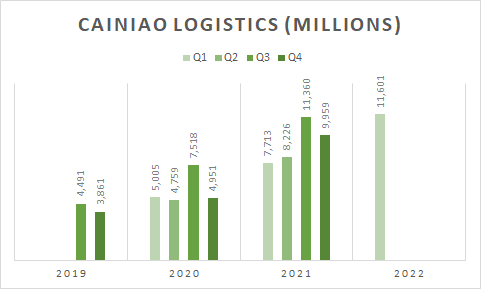

Their logistics services have been growing rapidly as it continues to expand both its domestic services and global smart logistics network by deepening integration with logistics partners as well as offering more products and services. Cainiao aims to deliver packages to anywhere in the world within 72 hours at an affordable price. If that happens, we should expect to see growth pick up on Alibaba’s e-commerce sites.

Consumer Services

Its consumers services apps comprise of three apps:

Ele.me is their version of UberEats and Doordash, an on-demand delivery service where consumers can order food and groceries.

Koubei is their version of Yelp, a restaurant and local services guide platform. It helps generate traffic to restaurants and other local service providers by offering consumers a ‘closed loop’ experience, from content discovery to finding the store to claiming discounts to payments.

Fliggy is their version of Booking.com, an online travel platform that allows for the booking of hotels and flights.

Their largest competitor for all 3 apps is Meituan’s super app and Meituan has been the leader in the online to offline consumer services field. Alibaba’s consumer services segment is a close second and it continues to grow steadily.

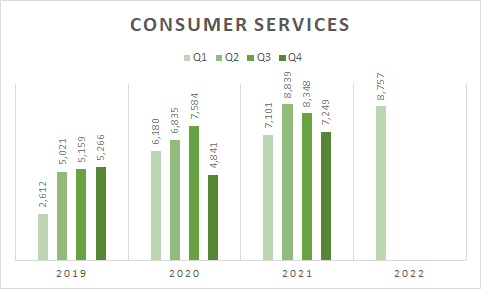

Alibaba’s consumer services segment has achieved very healthy year-on-year growth. From 2.6B RMB in Q1 2019 to 8.8B RMB in Q1 2022 represents an approximately 50% CAGR.

The Difference Between Amazon & Alibaba

Although we often hear people liken Alibaba to China’s Amazon. But other than being in e-commerce, they’re actually quite different.

Alibaba’s mission is 让天下没有难做的生意, which is to make it easy to do business anywhere. The company wants to be the facilitator of enabling small businesses. This means the bulk of their revenue comes from enabling third-party sales. Amazon, on the other hand, is focused on first-party sales. This means that Amazon will take inventory and sell directly to consumers.

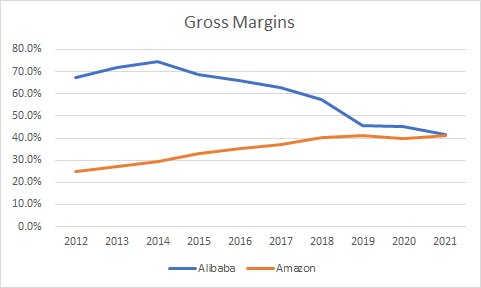

In Alibaba’s predominantly third-party model, there are several benefits, including higher margins and free cash flow since there are no inventories. When we look at Alibaba’s and Amazon’s gross margins in the early years going back to 2012, we can see that Alibaba’s margins is approximately 70% while Amazon’s margins is approximately 25% (I will explain why they converge later).

This is because Alibaba has no cost of goods sold (COGS) and makes most of its revenue through advertising or charging a commission off merchant’s sales (i.e. take-rate).

The other benefit is that Alibaba is able to scale at a much faster pace than Amazon. Because the first-party model will be constrained by capital and logistics because Amazon needs to buy the inventory and build out its warehouse because it can expand its reach. The first-party model is also a lot more capital intensive because the cost of laying out all these infrastructures requires a huge outlay at the start.

However, the downside to a third-party model is potentially worse user experience from fraud and fulfillment issues. When we look at world-class first-party e-commerce platforms like JD.com and Amazon, they have the capabilities to deliver in under a few hours and ensure that all products are authentic.

Over time, we see that both Alibaba’s and Amazon’s gross margins start to converge. At first glance, it might seem that Alibaba’s e-commerce business dynamics is worsening while Amazon’s are improving.

As always, we need to investigate and look under the hood.

For Alibaba, their decline in gross margins is not due to their e-commerce business declining. Rather, it’s due to their foray into new retail by heavily investing in the infrastructure (i.e. Cainiao) required and combining its hypermarkets into its books. This is why it appears to have dragged down its gross margins.

A decline in margins by itself may not be bad, if it is due to their third-party e-commerce business, I would be very concerned. But in this case, it’s because Alibaba is expanding into different verticals as they seek to dominate the online-to-offline experience, so there’s no reason to be alarmed.

For Amazon, it is not entirely because of their e-commerce profitability rising. Rather, it is from the success of their cloud computing division, Amazon Web Services (AWS) which is an extremely high margin business.

Regulations on Alibaba’s e-commerce

China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) accused the e-commerce juggernaut of violating the anti-monopoly law and imposing a record fine of 18.23 billion yuan (US$2.8 billion) for monopolistic conduct.

The fine is 4% of Alibaba’s 2019 domestic revenues (22% of net profit) and is recording-breaking. The previous record was Qualcomm in 2015 for $975 million.

China looks to the West (Europe in particular) for antitrust guidelines and this is in line with the fines European regulators have handed out for their antitrust lawsuits.

“Picking one from the two”

The fine was mainly for the ‘picking one from the two’ practice it imposed on merchants. This tactic forces online merchants to choose only one platform as their exclusive sales channel. For instance if I were to sell on Taobao, I can’t sell on JD.com.

If I were to violate this and sell on both Taobao and JD.com, I would be punished as a merchant as the platform blocks traffic to my page and bans me by taking my products offline altogether.

Chinese regulators have repeatedly warned about the practice for several years. Without the drastic measures, Alibaba and JD.com treated the regulators as “paper tigers” (纸老虎), we term used to describe someone who is all bark and no bite.

With the regulators removing the “picking one from the two” practice, merchants are now free to sell across platforms. My view is that it doesn’t affect Alibaba’s competitive advantage that much. As the biggest platform in China both in terms of the number of merchants and consumer traffic, Alibaba’s Taobao remains a very attractive platform for commerce to take place.

Consumers are more likely to visit a platform where there’s a large selection of products and buy from merchants with a good track record (i.e. number of sales, good ratings and reviews). Likewise, merchants will flock to the platform with the most eyeballs to market and sell their products. With such a robust e-commerce flywheel that Alibaba has been put in action, it is difficult for new entrants to enter and disrupt their model

Opening Up of Ecosystems

It is no secret that Alibaba and Tencent are nemeses and that they are at each other’s necks all the time.

Currently, WeChat (Tencent’s messaging app) bans all Alibaba’s links on its messaging app and mini-programs. If we were to send a Taobao URL onto WeChat, it will just disappear. In China, WeChat is the ‘app-store’ where you are able to access apps such as Meituan, Pinduoduo, Kuaishou directly on the WeChat app itself. This is also known as the WeChat mini-programs and it has helped apps such as Pinduoduo and Kuaishou take off by displaying them in prominent places.

For the longest time, they have banned all of Alibaba’s apps on its platform. But with the latest round of regulations, they’ll have to include apps such as Taobao and Ele.me onto its mini-programs and allow the URLs to be shared.

Likewise, Alibaba blocks all of WeChat’s URLs on its platform. In fact, it was Alibaba who started the ban on 1 Aug 2013 because Jack Ma understood the threat WeChat posed as a core communication and payments infrastructure. To compete with WeChat as China’s core communication platform, he took over Weibo and launched a WeChat clone called Laiwang which failed to grab market share over from WeChat.

Although the outcome hasn’t panned out to Jack Ma’s plans, those were the best moves available to him back then.

So who will benefit from the opening up of the ecosystem?

Let’s take a look at where the e-commerce apps are getting their traffic from.

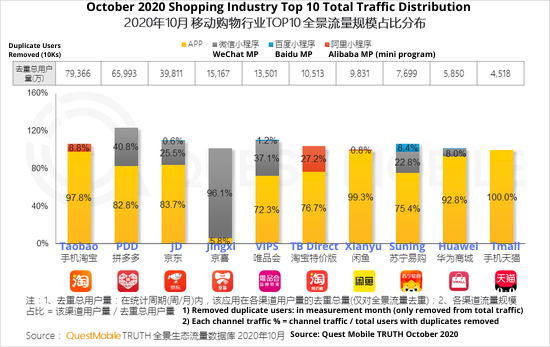

From the chart, it’s clear that Alibaba’s apps traffic are 100% organic while its closest competitor Pinduoduo and JD are deriving a sizeable amount of traffic of 40.8% and 25.5% respectively from WeChat’s mini-programs.

With 939 million MMAUs, it is very unlikely that Alibaba will gain more active users from the inclusion into WeChat’s mini-programs. Most people with a mobile phone in China already have its app installed. Likewise for WeChat, the inclusion into Alibaba’s ecosystem will not result in additional active users. In fact, it’ll be odd if anyone in China don’t have either one of these apps installed.

My guess is that Pinduoduo and JD might stand to lose out with the inclusion of Alibaba’s apps into WeChat’s mini-program, given that they get a sizeable amount of traffic from this platform. Consumers who usually shop on WeChat will be given more options and competition will be more intense for the existing e-commerce players reliant on WeChat’s mini-programs.

Cloud Computing

For Amazon, AWS was a home-run for the company. Cloud computing is a highly profitable business sitting on a giant tailwind and the most dominant players will seize most of the market share.

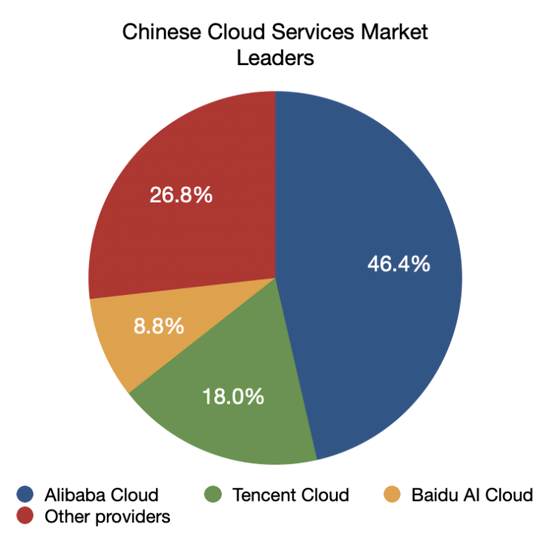

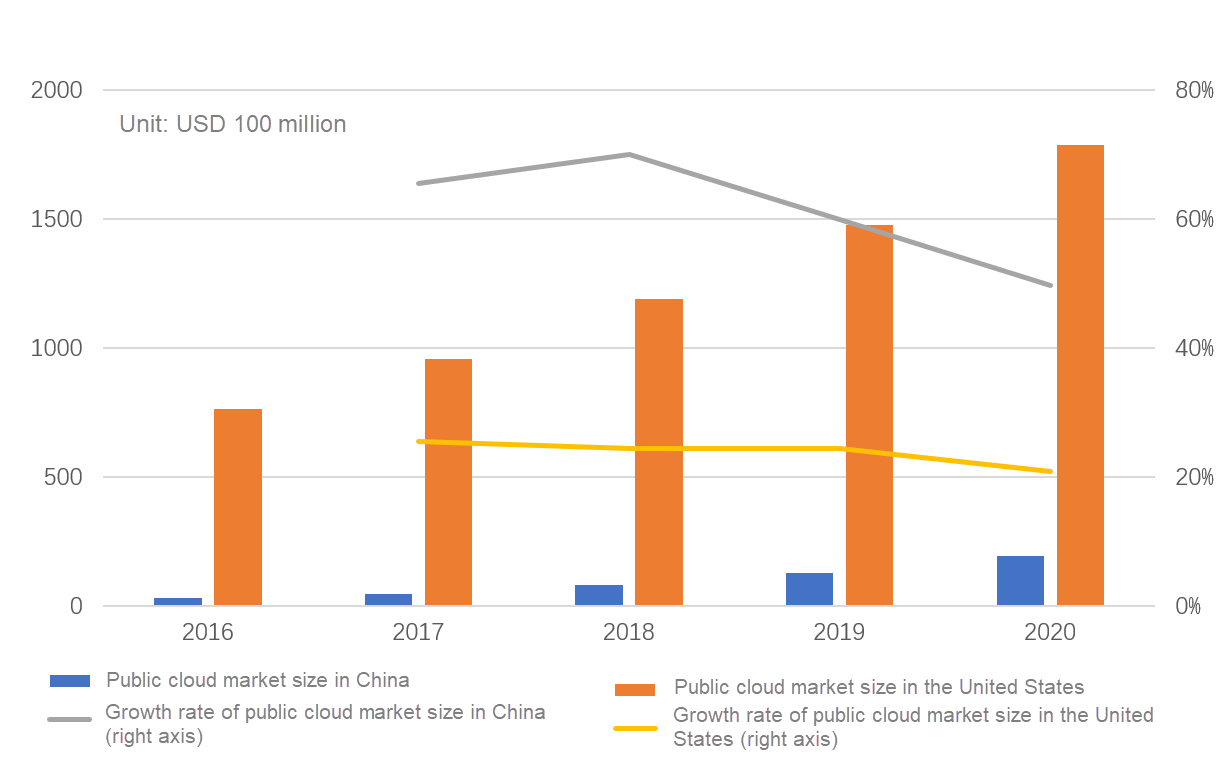

And Alibaba’s cloud computing division appears to resemble AWS many years back. The company has approximately half of China’s cloud market share and is sitting on a huge tailwind as seen in the chart below.

According to data from IDC, in 2020, the public cloud market size in China was USD 19.38 billion, which was only equivalent to 10.8% of that of the United States in the same year. However, in the past five years, the compound annual growth rate of China’s public cloud market has reached 61.1%, which is significantly higher than that of 23.8% in the United States.

Alibaba’s cloud usage was accelerated by the COVID-19 outbreak. Although China’s e-commerce is mature, its SaaS services (which are built on the cloud) are extremely nascent. For example, Alibaba’s DingTalk (China’s version of Slack and Microsoft Teams) had a huge growth in download rate with a staggering 1,446% increase. It enabled more than 200 million Chinese to work from home and about 50 million students’ home-based learning using the app.

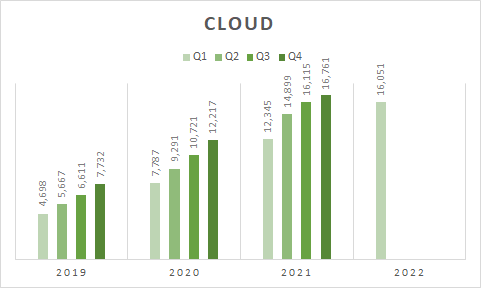

We see a slight dip from Q4 2021 to Q1 2022 because a top cloud customer (rumored to be Tik Tok) in the internet industry stopped using Alibaba cloud services with respect to their international businesses due to non-product-related requirements.

Generally, the cloud is regarded as a commodity service. Being a first-mover and also a big user has great advantages because the company is able to spread its fixed cost over a larger base and pass on the cost savings to consumers. With cheaper services, it’ll be able to attract more consumers and the flywheel will kick in.

Cloud is currently under 10% of Alibaba’s revenue and is expected to turn in profits by next year.

Conclusion

Alibaba is a company with numerous sprawling businesses and it would be impossible to cover them in one sitting. In this part one of the report, I covered the e-commerce business, the regulations that are affecting its e-commerce segment and the cloud business segment which accounts for the bulk of its revenue and profits. In the next report, I will go through Ant Financial and any other business segment, the impact of the regulations (especially for Ant Financial), risks and valuation of Alibaba.

Disclaimer: This research reports constitute the author’s personal views only and are for educational purposes only. It is not to be construed as financial advice in any shape or form. From time to time, the author may hold positions in the below-mentioned stocks consistent with the views and opinions expressed in this article. Disclosure – I hold a position in Alibaba at the time of publishing this article (this is a disclosure and NOT A RECOMMENDATION).

Become a member and gain access to to part II of Alibaba’s research report along with the entire archive of reports including Facebook, Twilio, Sea Limited, Crowdstrike and more!

hi Thomas, thanks for this insightful Part 1 deep dive of Alibaba. As BABA next quarter’s earnings has been moved to 18 Nov 2021 will you incorporate their latest results into your analysis of BABA ? I think it is important to have an upfront look on their performance after the recent CCP crack-down as the highest risk for the company is one of Political Risk and not so much to do with the company’s business qualities:)

Yeah definitely 🙂

Hi,

Enjoyed the write up, good work overall. Could you expand more on Cainiao? It has always been an enigma, how does Ali Baba manage it’s logistics. As Cainiao is off balance sheet (non consolidated), Ali Baba could be employing millions to carry on the logistics draining cash without even showing in their results (refer to Jim Chanos criticism in this regards). They do say that it is more of a platform/mediator between other logistics companies but this much is not clear. How does it work exactly?

Regards,

Thanks for the insightful article. Love your unique and transparent takes on key issues facing Alibaba. Regarding revival of walled gardens, I’m not convinced Alibaba wins if integrated in WeChat. Alibaba e-commerce predominantly makes money via selling search keyword rankings and display ads. That requires user to initiate search and spend time on the Alibaba apps to find and buy the product. If a direct link to the merchant can be marketed via WeChat that merchant won’t have incentive to spend marketing dollars on Ali ecosystem. It would rather pay WeChat because that’s where traffic will be coming from. This will become even more of an issue as under the pressure from CCP Alibaba has eliminated most of fixed fees to small merchants so it even more relies on ad revenue.

Wyatt are your thoughts on this?

Good point and great questions. I don’t think Alibaba would necessarily get more sales (% wise) from WeChat’s inclusion because of their large organic sales from their own platform. Rather, JD and PDD would suffer as they’re getting a significant portion of their sales from WeChat MP.

WeChat doesn’t take much ads (if any at all) on their platform. This is a decision they made to be user centric and not rank features based on who paid the most in ad dollars. So I don’t believe that it will affect BABA’s ad revenue.

A little sneaky, but they give more favorable placements to companies who allowed them to invest and take an equity stake. Now that the CCP is against this, shall see how this behavior evolves.