Often, management justifies huge mergers and acquisitions (M&A) with accretive earnings, asserting that earnings per share (EPS) would increase post-M&A.

Are accretive earnings a good measure of shareholder value?

After all, it seems to be the only thing analysts focus on when evaluating corporate deals.

One of the best ways to probe whether you can trust the advice that a theory is offering you is to look for anomalies—something that the theory cannot explain.

Earnings Accretive?

It does not matter whether earnings are accretive post-acquisition. In other words, whether the EPS goes up, down, or sideways in the short-term does not matter.

Consider this, if management puts $1 billion into fixed deposit earning 3% in interest. This generates $30 million in interest income immediately—an earnings accretive move.

But was it the best use of capital?

Bootstrapping

When a company with a higher P/E ratio acquires companies with lower P/E ratio using shares. This will increase the EPS of the combined business post-acquisition.

This practice is called bootstrapping. It is done to boost share prices without creating any real value to the business.

Let’s look at a simplified example to understand the concept:

In this scenario, the acquirer will have to pay $3,000,000 for the target company (market capitalization).

With the acquirer’s current share price of $100, it will have to issue 30,000 shares—derived by taking the $3,000,000 price tag divided by the current share price of $100.

Post-merger, the acquirer will have 130,000 shares outstanding. The combined entity’s net profit will be $600,000, with an EPS of $4.60.

This is an increase in EPS from $3 to $4.60!

As the acquirer had a higher P/E of 33 when compared to the target’s P/E of 10, it only had to issue 30,000 shares, as opposed to issuing an additional 100,000 shares.

The increase in EPS is due to financial engineering and synergies are not guaranteed. With rare exceptions, most M&As fail.

Companies that pursue growth through M&A to boost short-term earnings eventually have to face the music.

General Electric’s Shopping Spree

When Jack Welch took over General Electric (GE) in 1981, his goal was to become “the world’s most valuable company.” Welch turned his focus to the company’s share price.

He had an uncanny knack for beating analysts’ earnings estimates by a penny every quarter. Which is near impossible for a conglomerate the size of GE.

Welch grew GE into a super-conglomerate with acquisitions. His shopping spree masked many problems, which blew up after he left.

After Immelt took over, he continued to grow GE with the same playbook (M&A). Both Welch and Immelt justified deals after deals with earnings accretion, stretching the company’s balance sheet and cash flow.

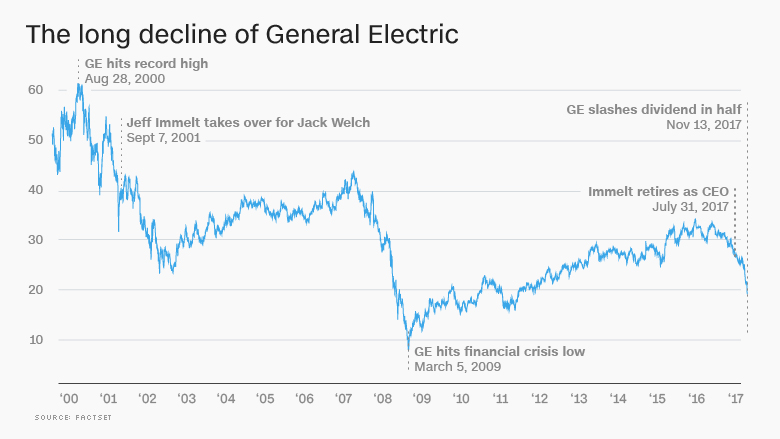

Immelt has since left, and GE is shedding businesses. Its share price has fallen from a peak of $60 in 2000 to $10 today.

Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor at the Stern School of Business, blamed Immelt for not moving more quickly and aggressively to shrink a maturing GE.

“Accept the fact you’re aging. Don’t fight it with acquisitions,” said Damodaran. “That’s like a 75-year-old doing a facelift. You can’t look good for long because gravity will work its magic sooner or later.”

Traits of Good Acquisitions

In Warren Buffett’s 1981 letter, he highlights the traits of good acquisitions:

The first involves companies that, through design or accident, have purchased only businesses that are particularly well adapted to an inflationary environment. Such favored business must have two characteristics:

(1) an ability to increase prices rather easily (even when product demand is flat and capacity is not fully utilized) without fear of significant loss of either market share or unit volume, and

(2) an ability to accommodate large dollar volume increases in business (often produced more by inflation than by real growth) with only minor additional investment of capital.

Buffett refers to high-quality compounders.

The first group are companies with strong brand equity such as Disney, Ferrari, or Hermès are able to raise prices without losing their market share to competitors.

Raising prices is powerful as it generates revenue without an increase in cost. It doesn’t demand a proportionate increase in raw materials, working capital, or building of new factories.

The second group are companies that are able to scale with little incremental capital investment. Think of Google—what is the additional cost for listing another ad on its search engine? Or Mastercard—what is the additional cost for handling another transaction?

Next to nothing!

The second category involves the managerial superstars—men who can recognize that rare prince who is disguised as a toad, and who have managerial abilities that enable them to peel away the disguise.

Here, Buffett talks about talented CEOs who are able to recognize good underpriced acquisitions. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg gets a lot of bad press, but he has been phenomenal in acquiring Instagram at only $1 billion in 2012 when it had no revenue. Its valuation has grown to $100 billion by 2018 according to a Bloomberg Intelligence report, becoming a 100-bagger investment for the firm.

Conclusion

Evaluating management’s M&A decisions is both an art and a science. It helps by first identifying what does not matter:

- Whether the transaction increases or dilutes EPS

- The P/E of the acquirer relative to the target’s P/E

Most acquisitions are earnings accretive but destroy shareholder value. The take home message for investors is this: go beyond focusing on short-term earnings and understand the rationale for management’s decision.

If management is not allocating capital soundly, reconsider your ownership in the business.